By integrating its legacy applications with the company's Web site,

National Gypsum was able to avoid having to buy new computers. "It

actually takes fewer people to manage the mainframe environment,"

says Peter McCaffrey, director of product marketing for the eServer

zSeries mainframe business at IBM.

In keeping with the craze to save via centralization, some companies

have been able to get rid of a dozen, or 50, or even 100 smaller

servers by rehosting all their systems on a mainframe.

Similarly, Winnebago Industries Inc. continues to roll along with

its big box. "It's typical for companies to have unused capacity

on the mainframe," says Dave Ennen, technical support manager at

the Forest City, Iowa, maker of motor homes.

The company has been able to run a number of newer Web-type applications

on its IBM mainframe without having to add servers. "We've had mainframes

here since the early 1970s, and we still have a lot of homegrown

applications running on there that are critical to our business."

But for companies without an existing investment in mainframes,

the continuing surge of new server technologies tends to drive data-center

design. Many are investing in powerful new machines called "blade"

servers that essentially contain the guts of several PCs packed

onto a single card (as opposed to the more "traditional" — if

one can use that word in IT — rack-mounted server unit).

Ultimately, these machines offer the power of a supercomputer at

far less cost. "Blade servers use very standard elements to optimize

space, power, and cooling," says Anil Vasudeva, president and principal

analyst at Imex Research in San Jose, California. The modular servers'

flexibility means they can be configured into various telecom, networking,

or storage modules.

Blade servers can be harnessed to run any number of computing power-hungry

applications, including the high input/output requirements of online

transaction processing, decision-support systems with online analytical

processing, and on-demand video-streaming applications that require

high bandwidth. The impact of blade servers "will be truly profound,"

adds Vasudeva.

Blades are very much in keeping with the continuing commoditization

of the server market. Low-end machines have plunged in price to

the point where some observers refer to them as "disposable." Once

expensive and bulky, today's servers are priced so low that if one

fails, it's more economical to replace it than to fix it.

In some cases, the spares are already installed in standby mode,

waiting to be switched on. Dell Computer Co.'s lowest-priced server

sells for $349, including rebates. As recently as the late 1990s,

most servers typically were priced in the $12,000 to $100,000 range.

Regardless of what hardware one finds in the data center, the odds

are increasingly good that it will be running some version of Linux,

the legendarily "free" operating system that seems to win new converts

— even among vendors — every day. Linux isn't totally free,

of course; when companies adopt it, they typically spring for maintenance

and support services in order to have a vendor on call. But there

is no license charge, and for that reason alone most large companies

are giving Linux at least a chance.

Some have found that its associated costs — such as consultants

to install it and hiring new employees or training current staff

to use it — can swallow up much of the savings. "We asked ourselves

if this could possibly be a replacement strategy to drive our costs

down," says Ann Turnbull, first vice president and IS manager at

Mellon Financial Corp., in Pittsburgh. "We figured that the cost

of conversion would outweigh any savings over a two-to-three-year

period."

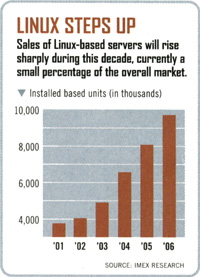

Despite a surfeit of media attention, Linux has not in fact taken

over the world; it accounts for just 5 percent of the server market.

But its momentum is unmistakable, and even Sun, which has long touted

its Solaris operating system, now offers Linux-based systems on

the low end.